In 1996, routine archaeological monitoring of building work in the Israeli city of Lod unexpectedly revealed a Roman mosaic that was unequalled in Israel and was one of the most impressive floors in the Roman world. News of the discovery spread, and crowds flocked to see the mosaic being uncovered. It was removed to allow a museum to be built on the site, and went on a world tour, enthralling visitors to the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and Waddesdon Manor in Buckinghamshire. The construction of the new centre required further excavation, and it was then that a second mosaic was found.

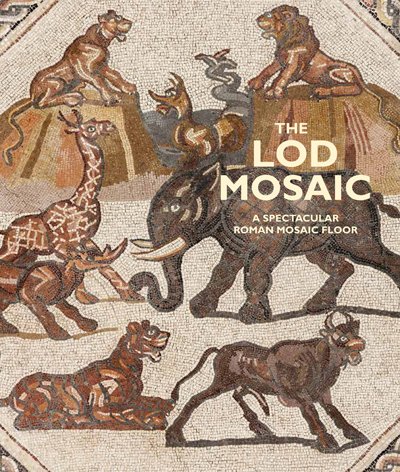

If you missed the mosaic at a venue near you, this book is the next best thing. Packed with stunning photographs of every part of the two mosaics, readers cannot fail to be impressed by the superb detail. Much of the book is devoted to key parts of the first floor, which was laid in the hall of a Roman town house. In the centre of the mosaic is a curious group of exotic beasts, a giraffe, rhinoceros, elephant and lion among them, all side by side in harmony. Surrounding this, and contrasting the central panel somewhat, are depictions of fish, game, and animals devouring other animals. A remarkable marine scene, complete with merchant ships, a terrifying whale, and fish recognisable to species, lies at one end of the floor. The second mosaic, laid in the town house's southern peristyle court, shows further images of fish, birds and preying animals, each contained in elegant octagons.

The authors contribute chapters on the historical background of Lod, the archaeology of the town house, and a discussion of the mosaics in their cultural context. Inevitably, given the multiple authorship, there are differences in interpretation. Glen Bowersock sees the central panel of the first mosaic as a reference to the peaceable kingdom, Isiah's prophecy in the Old Testament, at the same time alluding to the god Dionysus. Rina Talgam, meanwhile, sees the panel as a representation of African beasts destined for the amphitheatre. All agree that the mosaics were heavily influenced by North African traditions, yet prefigured styles that would develop in the Byzantine world.

The limited scope of the excavations means that there is little information about the house itself, its function and occupants (though some speculation is offered), and artefacts that must have been recovered from the excavations are excluded from discussion. While the book takes a strict art-historical approach, it lacks a sense of everyday life in Roman Lod. Nevertheless, the book provides an excellent description of the mosaics, and deserves a place on every Romanist's coffee table.