“The Kilbegly horizontal watermill is one of the most significant discoveries of its type in post-Roman Europe”. This is Colin Rynne’s view of the significance of this 2007 excavation by Valerie J Keeley Ltd on M6 motorway route through Co Roscommon. The book summarising this project is well illustrated by photographs and has a CD-ROM with excavation and specialist reports, plus the measured drawings.

Its director, Neil Jackman, describes the excavation of its shallow millpond, with boundary fences and an overflow system, which fed water c.0.7m down an inclined flume into the timber-floored undercroft of a mill-house. There, the wheel-hub of a horizontally rotating water-wheel, along with its drive shaft, plus two turbine paddles, were found together with a displaced timber, recognised as a ‘sole-tree’. The exiting water then ran c.5m along a level tail-race, before again dropping c.0.4m into a wider area, floored by a timber platform, presumed to be the site of an earlier horizontal mill.

In the specialist reports, Moore describes the woodworking techniques in the construction of the mill, whilst O Carroll examines how the woodland resources were exploited. Overland et al examine the environment, flora and fauna sampled during the project, noting an absence of locally grown cereals in the pollen record. Devane interrogates the historic archive, concluding that the mill ‘provided for the needs of the comarb who managed the termon lands that had been endowed by Ui Maine on [the monastery at] Clonmacnoise’. Two appendices summarise the other archaeological excavations along the c.20km route (a BA ring ditch, four burnt mounds and a late medieval cereal drying kiln) and also list the 45 radiocarbon dates obtained. Although 22 dates came from the mill (plus 5 dendro samples), no Bayesian statistics were attempted, leading Jackman to conclude that “the dating evidence indicates that the mill was built and used within the period from the mid-7th to the later-9th centuries [AD]”.

In the final section, Colin Rynne compares the new Kilbegly data with that previously recorded at some of the 130+ early medieval watermill sites known in Ireland. He highlights Kilbegly’s rare preservation of all the main elements needed to control the water supply, to route it down the flume, to direct the jet onto the paddles of the waterwheel and then to discharge the spent water. The undercroft timbers are similar to those at other contemporary mills. The grinding-floor implied above is only modest (c.2x2m). These dimensions are supported by a 2m long floor-plank.

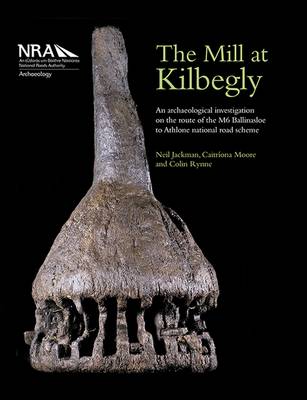

The complete timber wheel-hub is a welcome addition to the six Irish examples previously known and the intact (but broken) driveshaft is even rarer. Details of its construction, with the fitting of the 24 ‘scoop’ paddles are described. An ‘exploded’ diagram of the components (and a glossary of technical terms used) would have aided our comprehension. Restored at >93cm diameter, with a drive shaft length of 105cm (plus the unknown length of spindle/ rynd linkage to the upper stone), the waterwheel assembly is a substantial and intricate piece of wood carving. From the layout, the upper millstone was powered in a clockwise direction (as in the majority of R/B mills). No millstones were found, presumably due to their removal when the superstructure was dismantled. From data in the Nendrum report, the millstones were likely to be of ca 80cm diameter (McErlean, 2007, 177), so the ‘possible millstone fragment’ from the millpond, of c.28cm diameter, clearly had some other function.

Jackman & O’Keefe conclude that “the importance of Kilbegly resides in the fact of the survival of so much of its lower structure and operating system. It is, in every sense, a classic of its type”. As a probable asset of the monastery at Clonmacnoise, it provides us with a well-excavated and remarkably intact example of church-backed use of applied technology around the eighth century AD. With comparable Mid-Saxon watermills, such as Northfleet, Kent, whose construction is dendro-dated to AD691/2 (Andrews et al, 2011, 332), being generally less well preserved, this recent Irish evidence helps British archaeologists make more sense of their often fragmentary Early Medieval mill sites.

References

- Andrews P, Biddulp E, Hardy A & Brown R, 2011, Settling the Ebbsfleet Valley: High Speed 1 Excavations at Springhead & Northfleet, Kent: The LIA, Roman, Saxon & Medieval Landscape: Vol 1: The sites, Oxford Wessex Archaeology.

- McErlean T & Crothers N, 2007, Harnessing the Tides: The Early Medieval Tide Mills at Nendrum Monastery, Strangford Loch, N Ireland Arch. Monographs No 7, Stationery Office.