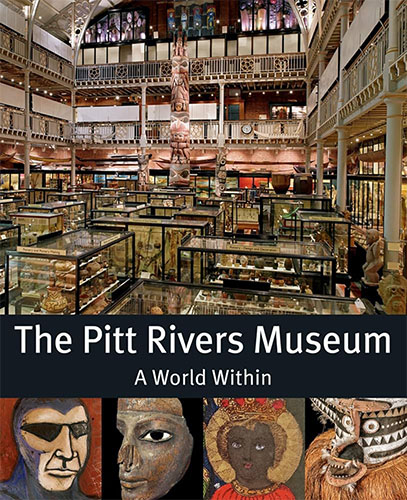

This striking book is beautifully designed with many eye-catching colour images; in this way it is very like the object of the author’s attentions. The Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford is stuffed with fascinating artefacts, many of which repay a second and third look; I am confident that readers will be compelled to return to both the book and the museum itself.

The author has been the Director of the Pitt Rivers since 1998, and he is well-placed to give a range of insights into the complexities of the history of the institution. O’Hanlon has an accessible style which will appeal to the casual reader – I sense that many copies of the book will be sold from the museum’s own bookstall – but there is enough substance here to engage those of us with a professional interest in museums and their development. He points out that pervasive understandings of the museum – that it is a single collection put together by its founder General A.H.L.F. Pitt-Rivers (1827-1900), that it is preserved in aspic as a reflection of Victorian aesthetic norms – are a very long way from the truth. Indeed, it is clear that visitors to museums (and perhaps, to an even greater extent, those who rarely set foot through the doors of these institutions) have a tendency to project their own chosen paradigm rather than fully engage with the reality of the layers of decision-making which lie behind the presentation of these exhibits in this arrangement in that location. The (in)famous ‘shrunken heads’ held at the Pitt-Rivers, which are, apparently, the most sought-out exhibits in terms of the frequency of questions put to museum staff, are a case in point. O’Hanlon gives a compelling account of the belief system which led to the creation of these objects, and sets out the ways in which the obvious interpretations, for example that these were much-prized battle trophies which should be returned to the tribes they were stolen from, are ill-founded. Even the tribes from whom the victims were taken would by no means inevitably welcome their ‘return’; this is a very clear object lesson which should prove useful to Critical Heritage courses.

If there is a criticism to be made of this book it is that many of the illustrations are decorative rather than strictly functional, in the sense that there is little discussion of most of them. In the same way there is not a great deal about archaeology: although the Pitt Rivers is described as a museum of anthropology and archaeology (p.17) the emphasis of the text and the images is more on the former than the latter. This is a reasonable compromise, though, as the chances are that the visitors to the Museum who are the target market of this book are more likely to be persuaded to make a purchase if the more eye-catching exhibits are prominent.