Many archaeologists become de facto semi-professional photographers because the medium is so integral to the process of recording sites, including buildings. Few of us, however, have any formal training in photography. There are plenty of general ‘how to’ publications available, but they will rarely be directly relevant to the situations we often find ourselves in. English Heritage’s 2006 good practice guidance is of course invaluable, but it is far more about standards (what we need to record – not just photographically – and why) than the methods and equipment we need to use.

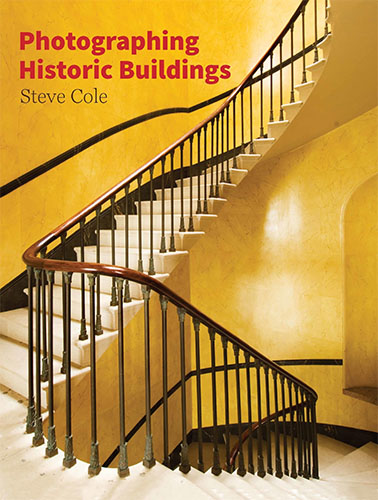

Thankfully Historic England evidently noted this gap in the market. Steve Cole, their Head of Photography from 2000 until his retirement in 2014, is among a select group who merit the title of professional archaeological photographer. As such he is ideally placed to write – and illustrate – a book like this. It is a welcome and important work, easy to read, and with a wide scope from first principles to post-processing of digital images. There is good advice on virtually every page, and a profusion of excellent images of buildings and their settings. One gripe here, though: details of the locations/subjects are only given in the picture credits at the end of the book rather than in the image captions. This is cumbersome and less than user friendly. This is less of an issue in the extensive section on case studies is very valuable here, as the author is able to expand on the details of how actual recording projects were approached – excellent ‘how I did it’ explanations. Details of how shots were lit (artificially and naturally) are particularly useful.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the book is very largely about digital photography. The early pages on the history of architectural photography and recording buildings obviously deals primarily with film media (it is a good potted history of the subject). From there on, however, the reality of modern photography - that most of it is digital – is accepted at least implicitly. The longevity of digital files, and their ‘readability’ in the future, is touched on but not conclusively – understandably, as it may be some years before the true permanence of digital files can be assessed. More advice could have been given, though, on the subject of printing our digital photographs. I probably take several thousand photographs every year: printing them all is impractical.

It is worth stressing that this is not a detailed manual. It does, however, include plenty of technical advice - on light temperatures and whether RAW is the best ‘archival’ format for digital photograph, for example, and also how to edit digital images back at your computer (saving the original files separately, of course). This is all very useful indeed, and I learned something new on most pages. Practicality is an important consideration when recording sites, however, as the book recognises. Its author had an enviably full suite of equipment available – flash units, lights, tripods and the like – as well as his cameras, and presumably the ability to transport such gear to any given site. I travel by train as much as I can, and therefore can’t manage much more than the tripod and a LED light panel. It is a testament to the brilliance of the cameras produced today by all major manufacturers that their products cope so well with the demands we make of them when recording buildings even if we sometimes have to limit the equipment we take on site.

This book provides excellent advice which is still relevant and useful even then.