This is the latest in the growing, and enjoyable, series of ‘in 20 Digs’ series by Amberley Publishing. This book (written by Worcester’s archaeological officer) looks at the key archaeological sites (or ‘digs’) from the historic city of Worcester. A short introduction gives an overview of urban archaeology in Wroxeter, and in general, from once a rescue pursuit by antiquarians at the whim of developers, to now a professional system embedded into the planning system.

Each chapter addresses one of the 20 chosen digs (a useful location map is provided), charting the development of archaeological work in the city from antiquarian records of the destruction of the castle motte in the 1830s, through to the New Cathedral Square excavation in 2015, that adopted methods to preserve the important remains in situ.

The first site discussed, the castle motte destruction in the 1830s, revealed a long sequence of reused defences from the Iron Age through to the 17th century Civil War (these were also recorded more recently in 2007-12 at King’s SPACE). The 1950s and 1960s post war slum clearance saw the first proper archaeological excavations. At Little Fish Street and Warmstry Slip the archaeologists were going in ‘blind’ without any clear knowledge of the archaeology of the area, it was their good fortune to hit upon a large Roman ditch, part of the northern defences of the Roman town. Some interesting archive photos show the trenches were impressively narrow and deep, with students working several metres below vertical sides, something that would not be acceptable today! The ditch was infilled in the late Anglo-Saxon period, when the burh defences were extended northwards.

A key archaeologist was Philip Barker, who was shocked by the levels of destruction of the archaeological remains at Worcester. He helped to found RESCUE, the British Archaeological Trust in the early 1970s, its main office was based in Worcester. Barker led an excavation at Lich Street (largely over the Christmas break whilst construction paused), discovering a well-preserved block of stratigraphy containing Iron Age, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, medieval and post-medieval activity, crucially utilising a variety of specialists (including Scouts to wash the finds!). Other important sites from the 1960s include evidence for a Roman ironworking industry, along with recording of Worcester’s medieval defences as they were largely demolished to make way for a road. Several hundred metres of wall remain visible to view, though this is often missed by visitors, due to the busy dual carriageway.

During the 1970s and 80s a standout excavation was the Sidbury and the Vue Cinema Site, there a good sequence of Roman activity was discovered, along with late Anglo-Saxon house plots and pits, and medieval industrial activity. This excavation highlighted the presence of deep deposits surviving in the city centre. Elsewhere, Worcester Cathedral was one of the first to appoint an archaeological consultant. Excavations in the Norman crypt recovered one burial known as the ‘Worcester pilgrim’ an elderly man found wearing leather boots, fragments of his woollen clothes still survived, along with a wooden staff. His boots and staff are on display in the cathedral. There is tantalising mention of new discoveries from more excavations in 2019-20 of building foundations dating to the Anglo-Saxon period, but no details offered. In the late 1980s the Deansway Excavation Project was one of the largest excavations in the city, where extensive remains were discovered. Early activity included an Iron Age roundhouse and horse burial, Roman streets, timber buildings and a cemetery. Importantly there was good evidence for dark earth soils, the Anglo-Saxon burh rampart, and buildings. There was also extensive evidence from the medieval period. The project was a watershed moment in Worcester’s archaeology history, being valued academically, archaeologically, and being of much interest to the general public through various outreach events. Worcester City Council shortly after appointed its first archaeological officer, and published a planning policy for archaeology.

After this there was a lengthy lull in archaeological activity, with no major excavations for nearly a decade. In 1997 the City Arcade development, was the first site in Wroxeter to have an emphasis on preservation in situ of the remains, with most excavation focused on the locations of the proposed foundation piles. A Roman mansio was partly investigated (with much of it preserved in situ). More recent discoveries included a good assemblage of eighteenth-century cesspits, to the rear of a pub, containing many wine bottles, mugs and tankards, and clay tobacco pipes. Evidence for a theatre too were uncovered.

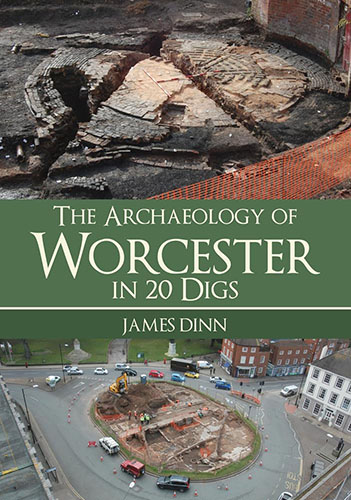

The first quarter of the 21st century have seen several significant archaeological investigations. In 2000, to the north of the city at Perdiswell, a Bronze Age palisaded enclosure was discovered. Roman discoveries include buildings (including a large 4th century aisled building), quarry pits, and a malting kiln. Notably recent medieval discoveries include medieval ovens and kilns, a hospital, post-medieval cloth-working, and a Civil War bastion ditch. Conversely, more recent archaeological remains include investigations at the Royal Worcester Porcelain Factory, these offer some details on the important 19th century factory, a 19th century brick-built porcelain kiln, and also evidence for dissection and surgical training in 19th century Worcester Royal Infirmary. The final project covered is from 2015, where post-medieval and early modern buildings were revealed directly below the ground in the middle of a roundabout. The new development designs allowed these remains to be covered over and protected, remaining in the ground for future archaeologists to explore.

The Archaeology of Worcester in 20 Digs offers valuable insight into the development of urban archaeology in Britain, from the perspective of one city, telling the story from individuals on watching briefs, to thorough professional assessments and excavations by large teams. The result is a great introduction to the most important archaeological sites in the city, along with some interesting more unusual archaeological discoveries. The book concludes with a further reading section. This book really is a good starting point for anyone interested in Worcester’s past, a good jumping off point into further more detailed reading into many different aspects of the historic Worcester.