This booklet (96 pages) on Roman gardens in the sense of leisure grounds, not market gardens nor orchards, is “intended as a popular introduction” (p. 5) and nicely sums up important archaeological results and textual evidence. It comprises an introduction, ten chapters, an aftermath, and a bibliography for further reading.

The earliest Roman town houses had little to offer in terms of gardens (p. 4), and it was only under Hellenistic inspiration that peristyle gardens developed at the heart of households and became an important prestige marker usually glimpsed right from the front door with lack of space compensated for by illusionist murals. Concepts of formal and geometric gardens coexisted with wilder Arcadian ideals, but water with its cooling effect, vivifying reflections, and gentle noises was an essential feature in either. In a culture with religion permeating all aspects of daily life (p. 7), it comes as no surprise that a pantheon of gods and immortalised heroes pervaded gardens. This included household gods, protective serpents, Venus, the goddess of beauty and rebirth, and fertility deities. Equally popular were water-related gods such as nymphs and arts-related divinities like the Muses. Another natural choice were the vegetation goddesses Diana, Flora, and Pomona.

While front gardens were rare, courtyards with pots, urns, raised flower beds, and plant holes were the rule (p. 13). Romans were virtually obsessed with “best views” (p. 16) staged by means of glass screens, huge windows or doors, and intercolumnia partly veiled by curtains. Gardens could be “hanging” on vaults or sunken to be viewed from above. Ephemeral trellises, pergolas, and fences were often illustrated as divisions, plant supports, and sunshades. Peristyle gardens were the prime location for displaying art collections (p. 25). Life-sized statuary was largely restricted to imperial, aristocratic, or public contexts, but ordinary gardens abounded with small-scale copies of famous sculptures, children, animals, Bacchic and bucolic scenes, evil-averting oscilla (rotating relief plates), herms (pillars with a head/bust), and pinakes (carved/coloured plaques on stands). Birdbaths, furniture, wellheads, sundials, wind chimes, lamps, and fountains were equally indispensable. On festive and religious occasions fresh floral garlands were added.

The non plus ultra of Roman gardening were the imperial gardens of the Palatine in Rome initiated by Augustus and continuously developed later (S. 47). Their water labyrinths, nymphaea, sunken peristyles, reflecting pools, hippodrome/stadium gardens, and mosaics served as models for representative gardens empire-wide, with Conimbriga actually rivalling Rome. Water gardens with canals, ponds, and islands became particularly popular (p. 62). The apex of Roman nymphaea was Tiberius’ seaside grotto at Sperlonga with Odyssean sculptural displays recreated or reflected at other imperial sites (p. 70). Plain nymphaea were often lunette-shaped in Africa and rectangular in the North. Finally, there were both fishponds (piscinae) with niches for spawning, with seawater fish being more prestigious than freshwater fish, and large square or fancy-shaped swimming pools (natationes, p. 81). Public gardens (p. 87) for walks and leisure of the less-privileged existed next to baths, theatres, porticoes, or temples.

The focus of the book is placed on Italy, the Iberian Peninsula, Northern Africa, and Britain, but evidence from Germany, Luxembourg, Turkey, Greece etc. is included occasionally. With regard to the emanation of the Sperlonga Grotto beyond imperial contexts, the unique high-quality sandstone reliefs of the Odyssey from a large water basin facing a German Villa urbana may be added (Enrico DeGennaro, Odyssee im Zabergäu. Die römischen Reliefs von Güglingen-Frauenzimmern. Schriftenreihe des Römermuseums Güglingen 5. Güglingen 2014).

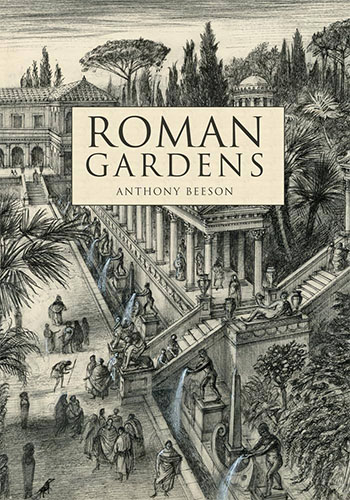

The volume offers a wealth of 114 illustrations including sixteen early excavation photographs with original garden decoration still in place and twelve skilfully crayoned drawings by the author himself. The only minor deficits are the absence of a glossary for technical terms and of an index of placenames. To make the best of this charming publication, it should be read on a summer’s day out in a park or garden with a fountain burbling along in the background. A veritable must-have for garden enthusiasts and admirers of the irenic aspects of ancient Rome alike!